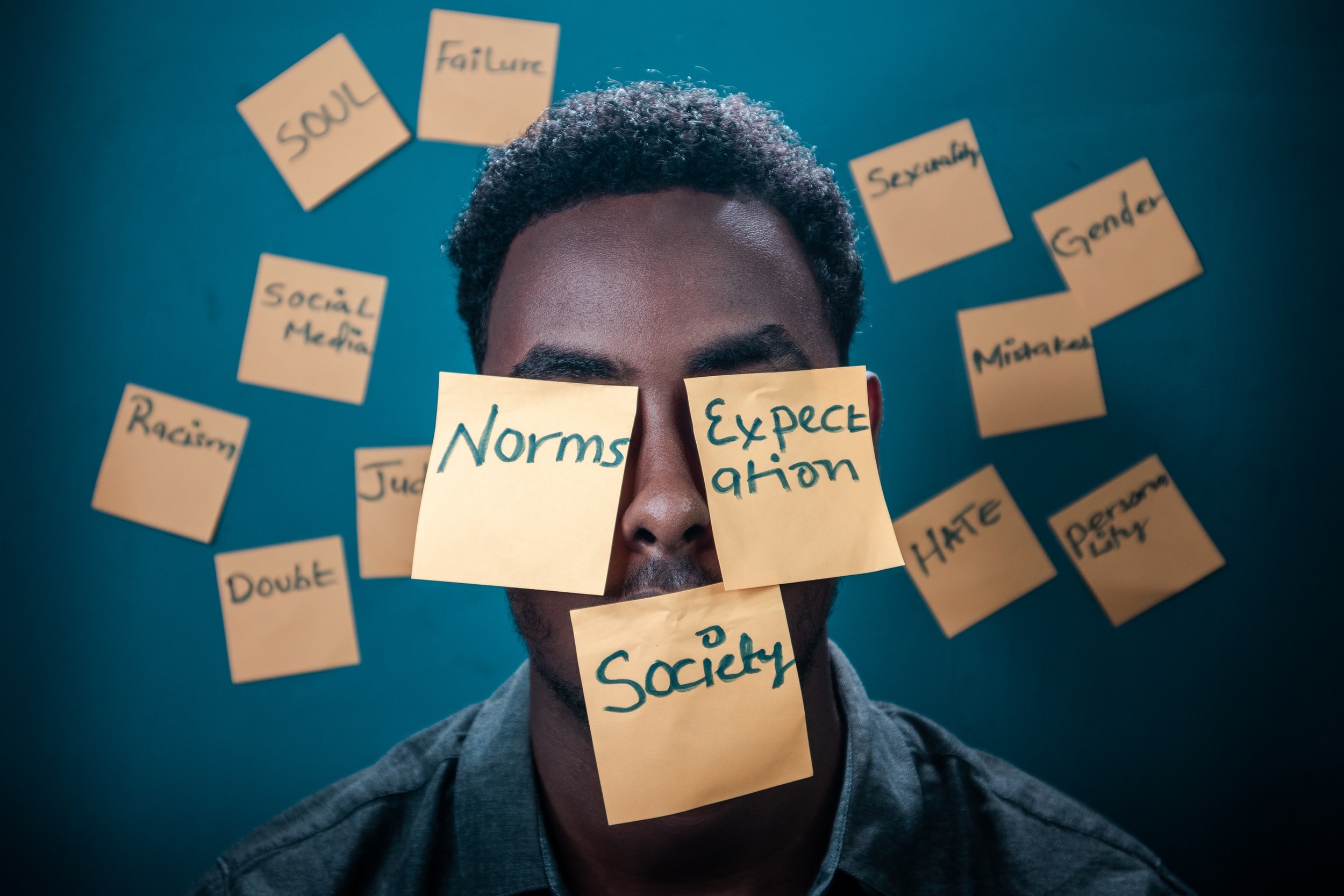

The limitations of virtual identities for underrepresented groups

Photo by Yasin Yusuf on Unsplash

Exploring the limitations of digital avatars

Due to the promise of technology in improving learning, VR is praised as revolutionising learning and “providing students with memorable and immersisve experiences that would otherwise not be possible” (“VR for Education - The Future of Education,” n.d.) and creating a more inclusive future (Allen, 2021). However, this optimistic vision does not benefit all groups. More so, report shows that the current discourse of a techno-utopia may not be the reality.

For example, in 2021, a metaverse female user wrote: “within 60 seconds of joining–I was verbally and sexually harassed– 3–4 male avatars, with male voices essentially, but virtually gang-raped my avatar” (Nkonde, 2022).

In a report, Bloomberg discovered that digital avatars with darker coloring sold for less than avatars with White traits. (Egkolfopoulou & Gardner, 2021). These events demonstrate that VR norms reflect offline norms as well (Martey & Stromer-Galley, 2007) and these norms can exclude/stigmatise users. This is supported by Freeman & Maloney (2020), who observed increased social stigma and racism towards avatars presenting as ethnic minorities. According to Harrell & Lim (2017), the biases of avatar-based systems are imposed both by the system and by users. In a VR game, for example, they observed that default values for avatars of African origin were optimised for brute force, and the avatars of European descent were optimised for intelligence. “The game”, concludes Harrell & Lim (2017), “is inequitable toward certain races in ways that replicate physical-world stereotypes” (p.56).

When using social VR applications, a young black person reflects on his choice to use avatars representing white ethnicity as a means of avoiding racist harassment. He explains:

“I can choose to get treated like a black person or not get treated like a black person—I'm probably going to choose not to get treated like a black person” (Blackwell et al., 2019).

It is evidenced then that “racial, gendered, and national differences are embedded, in both familiar and surprising ways, in a space described as a utopia free” (Philip, 2021). In the use of VR in education, this translates to a hidden curriculum that perpetuate hegemonic structures that marginalizes underrepresented groups and creates unfair learning environments. Since the system is biased, it creates a curriculum that serves the interests of dominant groups, excluding others, such as Black ethnic groups (Apple, 2019). This hidden curriculum forces underrepresented groups to see themselves through the prism of dominant groups, creating learning inequity which recognises the values/culture of dominant groups as the standard.

“Engaged scholars and designers who wish to shape future openness in internet infrastructures and cultures need to do more than affirm an abstract humanism in the service of universal technological access. Racial, gendered, and nationalist narratives are not simply outdated vestiges of past histories that will fall away naturally. The internet’s entangled technological and human histories carry past social orders into the present and shape our possible futures.”

Activity 1

Play the game, Chimera: Gatekeeper

I invite you to play the game - Chimera: Gatekeeper, an online game based on the work of the sociologist, Erving Goman, on social stigma. Goman’s hypothesis describes how stigma is constructed and maintained through social interaction. He introduces the concept of impression management to describe strategies adopted by the stigmatized when they mix with other groups.

Impression management involves a degree of self-surveillance in the presence of others, offline and virtually. How we present ourselves is driven by our intended audience. Thus, the stigmatized may develop a feeling of danger or anxiety that she or he will be “found out” as a fake.

The gatekeeper game simulates this phenomenon of impression management. It is a role-playing-game scenario where a player tries to gain access to the inside of a castle. The path to entry may demand that you choose to adapt to a social category or not. Your choice may lead to you hiding your identity so as to gain entry or accepted as a token.

The game attempts to capture the nuance and power relations that may occur in a virtual environment where the dominant culture or value is alien to an individual.

(“A Tale of Computing and Gatekeeping” by D. Fox Harrell CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

According to Gramsci (2000), hegemony is retained primarily through culture as the subordinate groups adopt the dominant group's values, beliefs, and perspectives. In sum, it is the normalisation of the status quo.

Consider these questions and share your answers in the padlet below:

Reflecting on the game or through your own experiences, how is hegemony sustained in perceived neutral contexts?

Does access provide equitable learning conditions? Explain the reasons for your answer.

Activity 2

In this video, scholar and founder of Critical Pedagogy, Henry Giroux, questions the notion of neutrality in education. He argues that neutrality is power at its worse, an invisible propaganda that hides the politics of dominant groups. He situates the advancement of technologies within a broader struggle between capitalism, democracy and power.

“All education is a struggle over what kind of future you want for young people” by Henry Giroux | Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (CC BY 4.0)

Reflection

Reflect on the following questions:

What effects might a learning environment have on a learner who has to engage in impression management?

How might digital avatars use ameliorate or exacerbate these effects?

Digital Avatar use and its impact on students from underrepresented groups by Henry Anumudu is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.